“Stems should not cross. C+” in red ink.

“Stems should not cross.” An elementary school teacher once wrote on the front of a picture I had made. I remember how her words discouraged me and made me fearful of making art. It is the only example of my childhood art that my parents saved, and it is something I continue to reflect upon, so in retrospect I am grateful that my parents saved it!

My perspectives about correction and critique changed as I took on different roles in life. As a student, I believe I steered clear from doing art, thinking, like many, that making art was for so-called “talented” people. This could not be further from the way I think now! As a young teacher, I believe I dwelled on the way that teacher had chosen to give me feedback. I was irritated that she had been so harsh when she wasn’t even an artist, herself. I also disagreed with her—I had seen a few stems crossing in the meantime! Later, as a more experienced teacher and a presenter on interdisciplinary work and teaching German through the arts, I credited that teacher to some degree for launching my research and public speaking career, and for influencing (by negative example) my pedagogical practices. She (and teachers like her) gave me plenty to talk about! Ultimately, I believe that those red letters and “C+” were even partly responsible for my strong desire to respect learners and to put thought into correction and critique. I wanted to model this for students.

It is important to reach students where they are, not where we want them to be. It is also important to provide feedback in a way that students are able to hear it. When students crave feedback, they can learn the most. In the language classroom, this means finding a way to correct students’ errors in a way that makes them invite correction without feeling self-conscious. Not only they, but also others around them, benefit from hearing errors and learning that there are various ways to express something. There are many ways to say and do things and becoming proficient entails learning to differentiate between meanings and register! In my ideal learning environment, students would be open to making mistakes and even thankful for them. I always said: “Make mistakes and make them early.” This is the best way to learn.

In UM RC Deutsches Theater, we did interdisciplinary work (combining theater, art, and German) to make perception, production, and reflection regular practices. Those three ways of knowing complement each other and they enable us to perceive things through multiple lenses and using various tools to chip away at meaning. Throughout experimentation or “production” we are constantly assessing, a process that involves both perception and reflection.

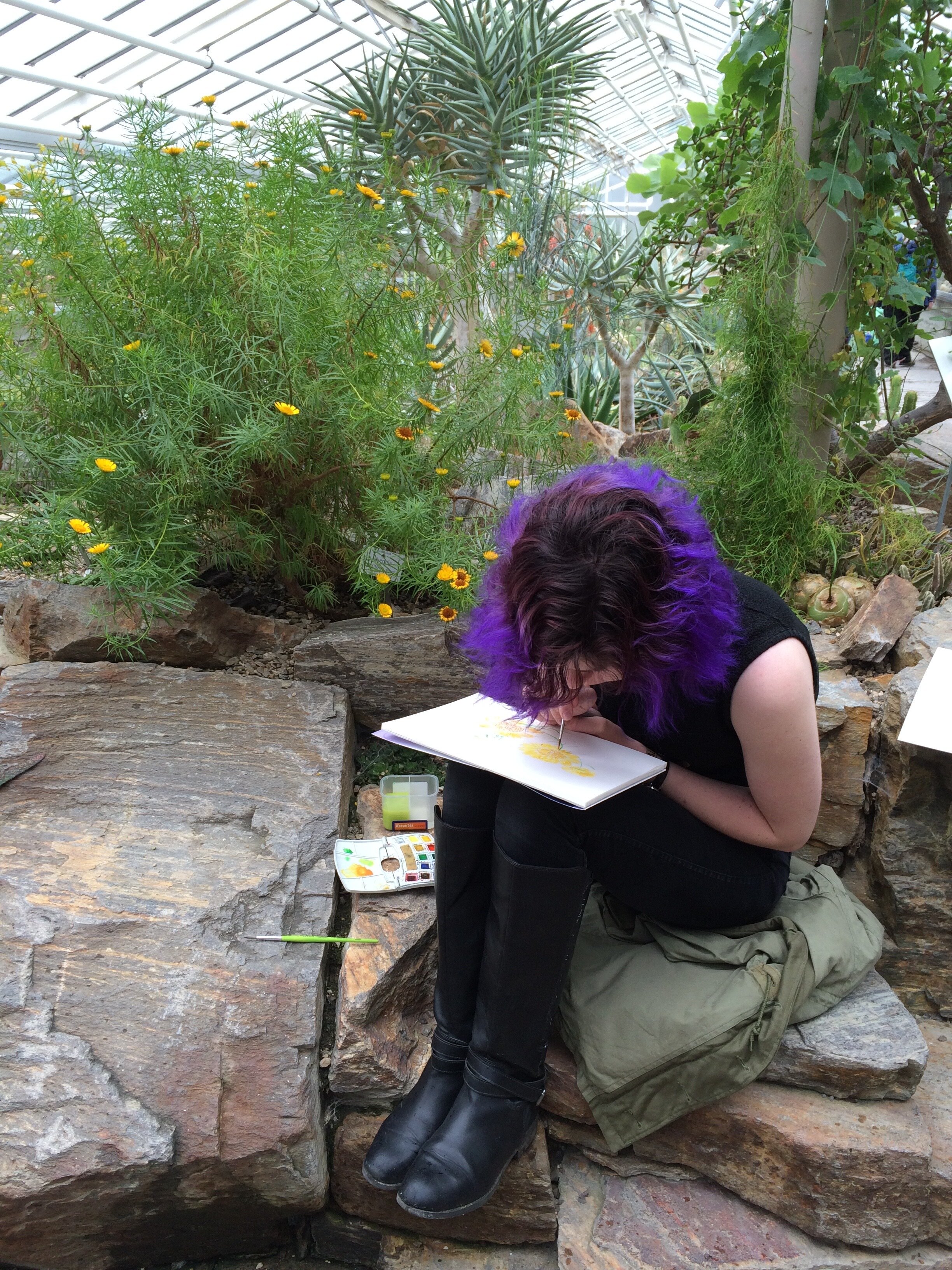

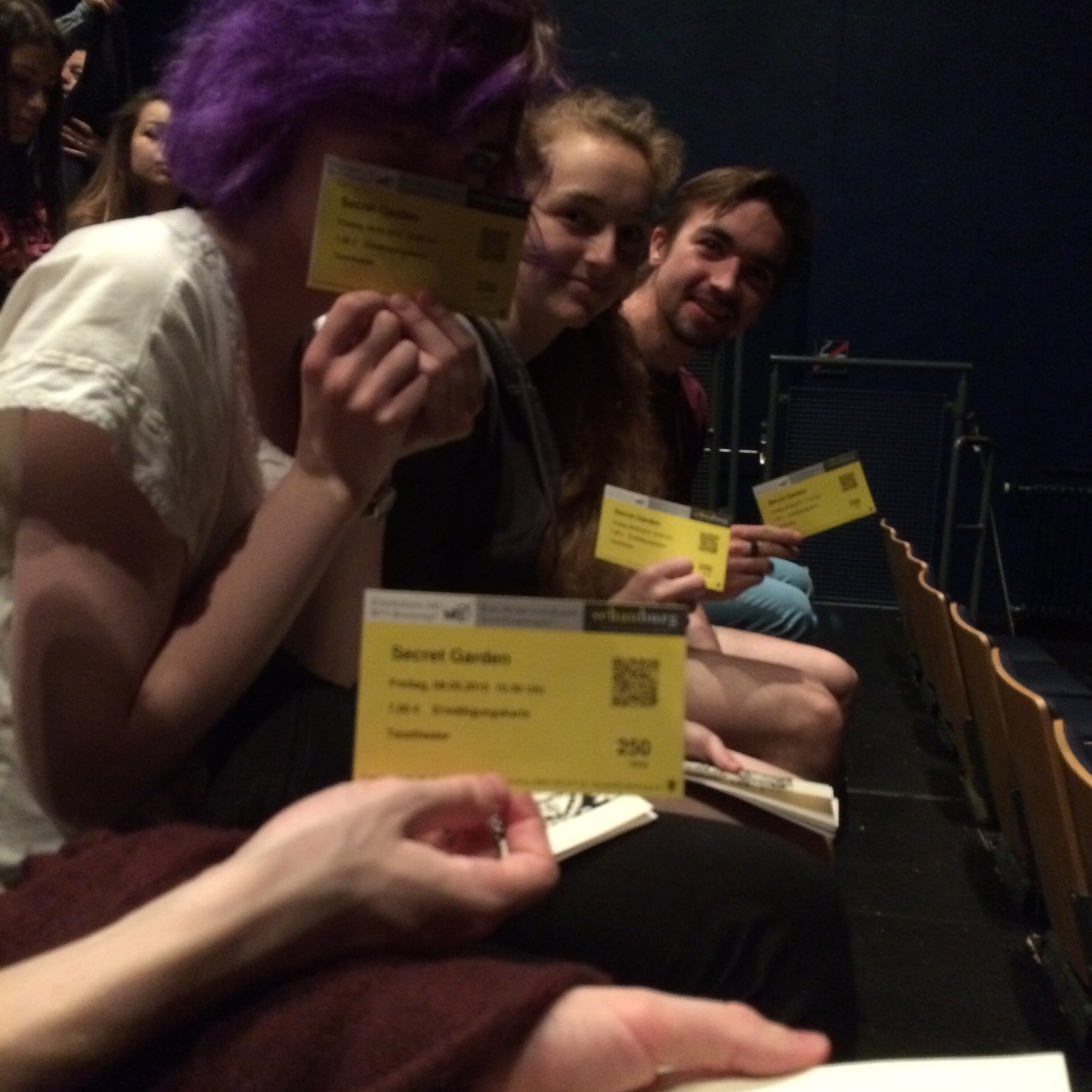

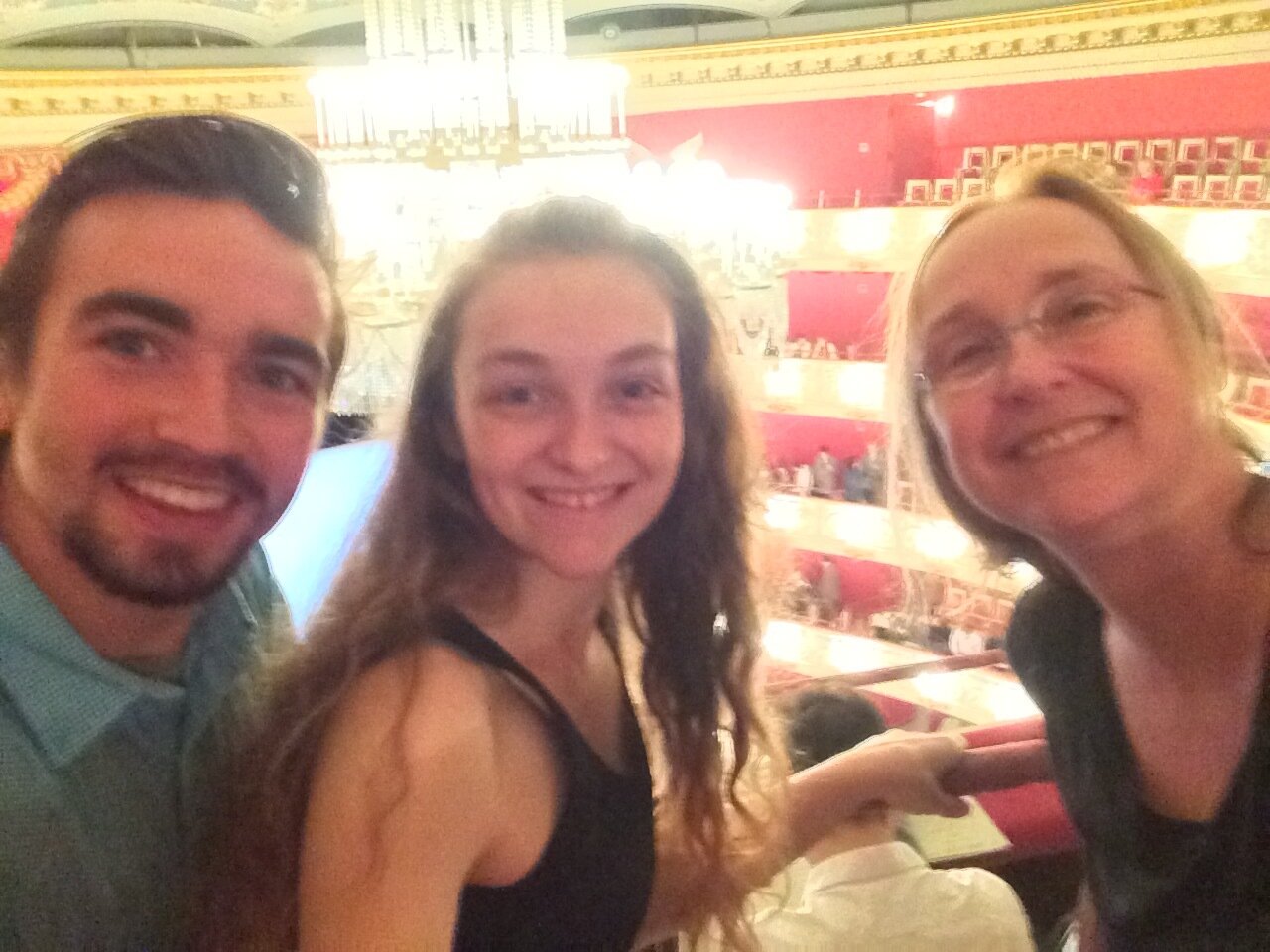

Creative work is essentially problem solving. It is block busting! Knowing this, helped my students look more closely at art to try to understand better. When we worked with German experts in their craft, my students felt comfortable accepting feedback. They accepted that Germans can be more comfortable being direct in their critique than some Americans are—this was a useful thing to learn! We saw professional theater and went to museums in Germany and also saw performances in unexpected sites and learned what an impact different sites of learning can have. Theater is performed in abandoned factories, in parks, in art museums. Art is in museums, in castles, in churches, and in the street. We interviewed actors, critics, curators, and artists; we drew and sketched in museums, in the countryside, and in theaters. We lived, breathed, and talked about art. We showed our art to each other and also sometimes to Germans, who were curious as they walked by. My students were not afraid of critique—they welcomed insights and understood that what others say can be useful, not judgmental. They learned to put things in perspective, something that is useful for every single aspect of daily life! The students, themselves, were not judgmental about others and they learned to not be judgmental of their own work, but to be more objective.

Once, we created Landart from nature as Germans strolled by and commented that they liked what we had created. This started a conversation. We spent the day creating found object art in nature. Some of the art was carried off by birds by the time we returned later in the day. The impermanence of our creations held the beauty of the process without diminishing the value of the product or the process.

The lessons here are many. But one thing I know for sure: it is vital to engage with life (even as a foreigner or even when one is not an “expert”). Everyone inevitably makes mistakes because that is necessary. It is how we learn. We learn best by doing, and should not fear taking good learning risks. So much of life is spent holding back. Trying something new, practicing mindfulness, and being patient with one’s own learning. . . this is what I call the freedom from and to oneself.

RC Deutsches Theater 2015 Study trip to Munich and the Alps, led by J.H. Shier. These photos illustrate the intersection of perception, production, and reflection, three ongoing processes critical to the arts and to learning. Photos ©2015Janet Hegman Shier, Malaika Press. Please do not use or distribute without permission.